Ourland

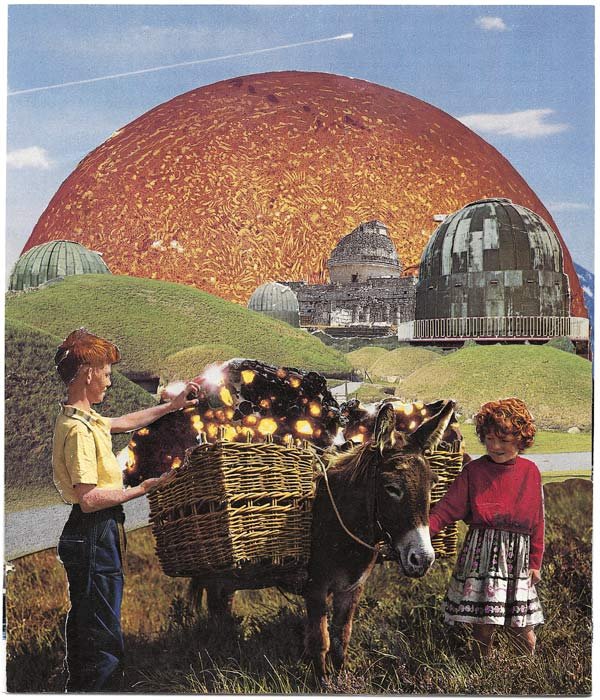

Collecting Meteorites at Knowth - Sean Hillen

It was October. We arrived late and began the climb; guided along the way by echoes of a thrashing guitar. The Fontaines D.C were in London, they were inside Alexandra Palace and I was about to see them play for the first time. What follows is not a review of their performance late last year. Instead, it’s a reflection on something else displayed that night; something that made me think about popular Irish culture and how it’s evolved.

Haunted by folds

When I was younger, Irishness was a thing my friends ignored. It was American culture and in particular rap, that was considered cool. When 50 Cent released ‘In da club’, I remember pretending to know the lyrics to each track and asking my parents for a pair of G-Unit shoes. The album mesmerised my primary school; reducing huddles of 12-year-old boys to solemn head-bops and emphatic recitals. But there was also Redzer, a rapper from Ballymun who came to prominence around 2006 and was often derided for his heavy Dublin accent. Somehow, when rap was performed by Redzer, it seemed less authentic; it was closer to home and yet harder to believe.

In 2024, things look very different. The recent popularity of artists like Kojaque, For Those I Love and The Fontaines D.C is evidence of a C-change regarding what’s cool. The accent, the localised lyrics and the embrace of themes that are often politically charged demonstrate an embrace of our Emerald Isle as both a nation and a social identity. An aesthetic of nostalgia now seems to reverberate and hit home. But why is this? What have been the moments that led to this reinvigoration of national pride? To look for an answer we need to step back in time and reflect on Irish culture as it evolved throughout recent history.

Isaiah Berlin once argued that history “moves not in continuous straight lines, but in folds. These folds are not of equal length or substance, but if we venture to examine the points at which these folds touch one another, we will often find strong and real similarities between the points”. Evidence of this idea, that the past resonates with our sense of the present, is said to grow as we age. What I witnessed at Alexandra Palace that evening felt uncanny and left me nostalgic for a time I never lived through. That exact moment, as far as I can tell, was somewhere around the late 1970s. The Boom Town Rats, the Pogues and Joy Division appeared as ghostly supporting acts, hovering around the venue as the crowds began to exit. Men in their 60s had grinned with clenched pints and looked exhilarated by resurrected feelings of youthful novelty. Teenagers, too, seemed equally in awe of what they had seen. But for them, the novelty of the act was paradoxically the revival of something that had ceased to be novel.

The death of romance

The historian Roy Foster has remarked on the immense rate of change in Ireland from 1970 to 2000. From the late 1960s, the country started to embrace liberal ideas of individual agency and civil rights. This moment chimed with progressive movements across the globe and prompted a reaction to the all-consuming overreach of the Catholic Church. Pushback took many forms - political, social and cultural - but in the widest sense, there was a shift in public attitude towards authority. Clerical conservatism was challenged by a fledgling secular and feminist front that Foster has described as ‘…lower case p…protestant’. Modernity had arrived. Solidity was melting into air.

Alongside these cultural tremors came a new, global outlook, that coincided with Ireland’s entry into the European Communities in 1973. Nationalism and Catholicism had been indivisible during the time of dé Valera. Yet, with the broadening horizons that accompanied continental unity, a rift between church and state arose that sparked a slow, but steady, re-evaluation of Irishness. In 1980, U2 released their debut album, ‘Boy’, and in doing so, presented this burgeoning identity. Described as post-punk at the time, the sound was unencumbered by the baggage of the past. U2 followed a growing trend set by British acts like The Fall and Gang of Four who were striving to rid their work of precedent.

The era of ‘Boy’ coincided with growing resentment toward the gradual commodification of Irish culture. In the 1960s, Bord Failte had aimed to draw in (largely) American tourism by collaborating with US corporations. The result was marketing that wholeheartedly embraced anachronisms; “The hills are as green as they’ve ever been. Life is as quiet as it ever was. And time has a way of standing still. Let Pan-Am take you there”. Although life in Ireland was anything but still as the 21st Century began to loom, Bord Failte’s effort to grow international tourism resulted in masterful branding that distilled the nation into a highly palatable aesthetic.

The image of Ireland that came to the fore espoused the conceptions of Yeats and took illustrative shape through the postcards of John Hinde (later mocked by Sean Hillen’s montages in the 1990s). But this aesthetic was at odds with the modern and later post-modern movements that were steadily gathering popular momentum. The tension between what the country truly was and how it should be portrayed spurred a moment that Foster has called ‘The slow death of romantic Ireland’. The relentless effort by artists like U2 to turn away from the past was emboldened by their conviction that history was kitsch. As the nation grew wealthy and the economy sky-rocketed, all that mattered was the future. The temporal nature of modernity reduced the present to a flicker of change and within this context, cultural introspection lost its way. Romanticism had no place at the end of history.

Getting to know ourselves

In hindsight, it appears that my primary school cringe at Redzer was symptomatic of a broader public sentiment that had been in development since the 1970s. Two years after I reached secondary school, this sentiment shuddered to a halt and began to decline. In 2008, the financial crash rocked the globe and spelt the demise of what Gary Gerstle has called ‘The Neoliberal Order’. In Ireland, government levies on income and propositions to raise university fees resulted in widespread protest that included student marches and the Occupy Movement establishing itself in Dublin, Cork, Waterford and Galway. Austerity had arrived and political unrest returned to the nation. As the bubble burst, its effects began to raise their head in cultural as well as political spheres.

Hozier’s 2014 release ‘Take me to church’ re-established the well-trodden themes of original sin and anti-authority that were so prominent during the civil rights activism of the 1970s. Following the Eurozone crisis and the ensuing public bailout, these themes had risen back to the surface. This time, however, our wrongdoing lay not in calls for sexual liberation, but in the collective greed of the Celtic Tiger. Our penance was austerity and the elites overseeing things resembled a new form of technocratic clergy. The 2011 general election resulted in Fianna Fail suffering one of the worst defeats of any Western governing party in history. The nation had spoken, the verdict was change and the clerics came tumbling down.

Amid the raucous of the period emerged calls for a referendum on matters previously side-lined when the going was good. The crumbling political hegemony of Fianna Fail shifted public discourse to matters of social liberalisation. Three years after the landslide success of the Marriage Equality Act, Repeal the 8th followed suit. These constitutional amendments evidenced an immense rejuvenation of civic engagement in Ireland. Young people had taken to the streets and flexed their democratic agency with demands for a better future. Within this context, there appeared the curious revival of something buried at the latter end of the 1980s; ’Romantic Ireland’.

When the Fontaines D.C burst onto the scene with their 2019 release; ‘Dogrel’, they swooned the Repeal generation with elegiac anthems of Dublin and an energised sense of nostalgia. Yet, given the unprecedented social progress in Ireland, why was it that nostalgia, of all things, should catch on? Irishness, it seemed, no longer evoked the twee and conservative connotations of the past. Perhaps the folds of history were touching again as public agency grew in force? Did the failures of globalisation press upon us the feeling that somewhere along the way we’d lost our true sense of national identity? And amid this moment of disorientation, anger and sadness, did we look to history for stability and find within it a mere array of imagery on which to lean? Punk rock and The Dubliners, Gaeilge, Guinness and colonial oppression. Jpegs of Irishness. Retweeted and remixed by Blindboy, Instagram artists and the Fontaines D.C. If Ireland was lost, was it Google that would find it?

This reflection aims to present the necessity of important questions; how do we reinvent the future? How do we define our land? As always, maybe history can guide us to revelation. After all, as the late Mark Fisher once put it; “Those who can't remember the past are condemned to have it resold to them forever”.