On Crockadoon

A short story

I used to ask about his prefix - what made him ‘grand’ - and her cheeks would crease and laughter would pour in my direction. She told me it was simple. ‘Grand’ only meant ‘old’. And because it made her laugh, I liked to bring it up. But then, for a time, he was barely mentioned. Until one day, in late July, she told me he was gone. And I remember her cheeks creasing again; but this time, it was pain that poured; her eyes narrowed and skin glistened.

-

Before he passed, we packed and drove to Crockadoon. The city had simmered that year - cloaked in viscous air that dragged at limbs. We drank cold tea and opened windows. But it was too much, and one morning she told me we were leaving.

Light had pooled, that day, in the valleys of my bedroom curtains, and saturated them until they glowed. As we left, something of that glow stayed with me; hovering in my vision, fixing itself with every blink to something new.

We arrived late, and Crockadoon was split by shade. The sunset tipped its rocky crenelations and cast, onto the fields below, a serrated edge. In the distance, the sea was feathered with spray. We followed the undulations that led to the old house and, at the gate, I got out and directed her down the driveway. For hours, we sat up and had little to say. But just before midnight she smiled and told me it was time for bed.

Days passed and we walked and swam and went into town. On Sunday, we sat through mass and spoke, afterwards, to a blur of faces. The air was cooler and it cooled our senses. She seemed hushed by the wind and the percolating rain. And in the evenings, as she read the paper, I would curl at her feet and listen to her murmur. But in her eyes I could see another horizon; a thought that she would not express.

It came one day when I least expected. The weather had changed and Crockadoon roared the arrival of rain. Bound indoors, we took turns reading passages of old books and drawing pictures of each other. Blanketed by the sound of the storm one evening, I left my bedroom and crept across the hallway. She was sat in the kitchen, slumped forward, poring over photographs. I lingered for a while, then turned to leave. But upon moving, she looked up and caught the reflection of my eyes in the window.

“Michael” she said.

I said nothing.

In the days that followed, the rain subsided and the air was dense with the smell of earth and leaves. As the house dried, the floors became cool; the windows glazed with dew.

To escape the damp, she suggested we climb Crockadoon. And a day later, beneath a granite sky, we did. We curved and wound our way through gorse and shale, and she moved with slow intention. At the summit, the sea spread out like hammered glass. She closed her eyes, and for a moment I thought she might speak. But then she turned and smiled and Crockadoon spoke for her.

Ourland

A reflection on Ireland and identity

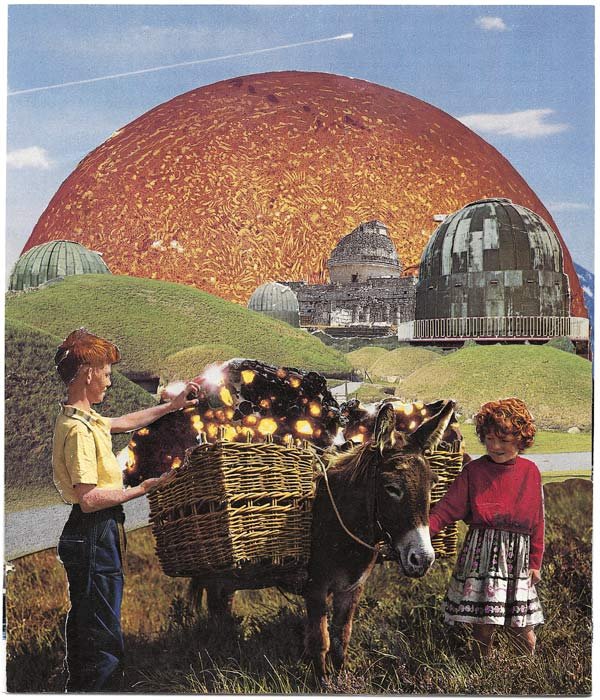

Collecting Meteorites at Knowth - Sean Hillen

It was October. We arrived late and began the climb; guided along the way by echoes of a thrashing guitar. The Fontaines D.C were in London, they were inside Alexandra Palace and I was about to see them play for the first time. What follows is not a review of their performance late last year. Instead, it’s a reflection on something else displayed that night; something that made me think about popular Irish culture and how it’s evolved.

Haunted by folds

When I was younger, Irishness was a thing my friends ignored. It was American culture and in particular rap, that was considered cool. When 50 Cent released ‘In da club’, I remember pretending to know the lyrics to each track and asking my parents for a pair of G-Unit shoes. The album mesmerised my primary school; reducing huddles of 12-year-old boys to solemn head-bops and emphatic recitals. But there was also Redzer, a rapper from Ballymun who came to prominence around 2006 and was often derided for his heavy Dublin accent. Somehow, when rap was performed by Redzer, it seemed less authentic; it was closer to home and yet harder to believe.

In 2024, things look very different. The recent popularity of artists like Kojaque, For Those I Love and The Fontaines D.C is evidence of a C-change regarding what’s cool. The accent, the localised lyrics and the embrace of themes that are often politically charged demonstrate an embrace of our Emerald Isle as both a nation and a social identity. An aesthetic of nostalgia now seems to reverberate and hit home. But why is this? What have been the moments that led to this reinvigoration of national pride? To look for an answer we need to step back in time and reflect on Irish culture as it evolved throughout recent history.

Isaiah Berlin once argued that history “moves not in continuous straight lines, but in folds. These folds are not of equal length or substance, but if we venture to examine the points at which these folds touch one another, we will often find strong and real similarities between the points”. Evidence of this idea, that the past resonates with our sense of the present, is said to grow as we age. What I witnessed at Alexandra Palace that evening felt uncanny and left me nostalgic for a time I never lived through. That exact moment, as far as I can tell, was somewhere around the late 1970s. The Boom Town Rats, the Pogues and Joy Division appeared as ghostly supporting acts, hovering around the venue as the crowds began to exit. Men in their 60s had grinned with clenched pints and looked exhilarated by resurrected feelings of youthful novelty. Teenagers, too, seemed equally in awe of what they had seen. But for them, the novelty of the act was paradoxically the revival of something that had ceased to be novel.

The death of romance

The historian Roy Foster has remarked on the immense rate of change in Ireland from 1970 to 2000. From the late 1960s, the country started to embrace liberal ideas of individual agency and civil rights. This moment chimed with progressive movements across the globe and prompted a reaction to the all-consuming overreach of the Catholic Church. Pushback took many forms - political, social and cultural - but in the widest sense, there was a shift in public attitude towards authority. Clerical conservatism was challenged by a fledgling secular and feminist front that Foster has described as ‘…lower case p…protestant’. Modernity had arrived. Solidity was melting into air.

Alongside these cultural tremors came a new, global outlook, that coincided with Ireland’s entry into the European Communities in 1973. Nationalism and Catholicism had been indivisible during the time of dé Valera. Yet, with the broadening horizons that accompanied continental unity, a rift between church and state arose that sparked a slow, but steady, re-evaluation of Irishness. In 1980, U2 released their debut album, ‘Boy’, and in doing so, presented this burgeoning identity. Described as post-punk at the time, the sound was unencumbered by the baggage of the past. U2 followed a growing trend set by British acts like The Fall and Gang of Four who were striving to rid their work of precedent.

The era of ‘Boy’ coincided with growing resentment toward the gradual commodification of Irish culture. In the 1960s, Bord Failte had aimed to draw in (largely) American tourism by collaborating with US corporations. The result was marketing that wholeheartedly embraced anachronisms; “The hills are as green as they’ve ever been. Life is as quiet as it ever was. And time has a way of standing still. Let Pan-Am take you there”. Although life in Ireland was anything but still as the 21st Century began to loom, Bord Failte’s effort to grow international tourism resulted in masterful branding that distilled the nation into a highly palatable aesthetic.

The image of Ireland that came to the fore espoused the conceptions of Yeats and took illustrative shape through the postcards of John Hinde (later mocked by Sean Hillen’s montages in the 1990s). But this aesthetic was at odds with the modern and later post-modern movements that were steadily gathering popular momentum. The tension between what the country truly was and how it should be portrayed spurred a moment that Foster has called ‘The slow death of romantic Ireland’. The relentless effort by artists like U2 to turn away from the past was emboldened by their conviction that history was kitsch. As the nation grew wealthy and the economy sky-rocketed, all that mattered was the future. The temporal nature of modernity reduced the present to a flicker of change and within this context, cultural introspection lost its way. Romanticism had no place at the end of history.

Getting to know ourselves

In hindsight, it appears that my primary school cringe at Redzer was symptomatic of a broader public sentiment that had been in development since the 1970s. Two years after I reached secondary school, this sentiment shuddered to a halt and began to decline. In 2008, the financial crash rocked the globe and spelt the demise of what Gary Gerstle has called ‘The Neoliberal Order’. In Ireland, government levies on income and propositions to raise university fees resulted in widespread protest that included student marches and the Occupy Movement establishing itself in Dublin, Cork, Waterford and Galway. Austerity had arrived and political unrest returned to the nation. As the bubble burst, its effects began to raise their head in cultural as well as political spheres.

Hozier’s 2014 release ‘Take me to church’ re-established the well-trodden themes of original sin and anti-authority that were so prominent during the civil rights activism of the 1970s. Following the Eurozone crisis and the ensuing public bailout, these themes had risen back to the surface. This time, however, our wrongdoing lay not in calls for sexual liberation, but in the collective greed of the Celtic Tiger. Our penance was austerity and the elites overseeing things resembled a new form of technocratic clergy. The 2011 general election resulted in Fianna Fail suffering one of the worst defeats of any Western governing party in history. The nation had spoken, the verdict was change and the clerics came tumbling down.

Amid the raucous of the period emerged calls for a referendum on matters previously side-lined when the going was good. The crumbling political hegemony of Fianna Fail shifted public discourse to matters of social liberalisation. Three years after the landslide success of the Marriage Equality Act, Repeal the 8th followed suit. These constitutional amendments evidenced an immense rejuvenation of civic engagement in Ireland. Young people had taken to the streets and flexed their democratic agency with demands for a better future. Within this context, there appeared the curious revival of something buried at the latter end of the 1980s; ’Romantic Ireland’.

When the Fontaines D.C burst onto the scene with their 2019 release; ‘Dogrel’, they swooned the Repeal generation with elegiac anthems of Dublin and an energised sense of nostalgia. Yet, given the unprecedented social progress in Ireland, why was it that nostalgia, of all things, should catch on? Irishness, it seemed, no longer evoked the twee and conservative connotations of the past. Perhaps the folds of history were touching again as public agency grew in force? Did the failures of globalisation press upon us the feeling that somewhere along the way we’d lost our true sense of national identity? And amid this moment of disorientation, anger and sadness, did we look to history for stability and find within it a mere array of imagery on which to lean? Punk rock and The Dubliners, Gaeilge, Guinness and colonial oppression. Jpegs of Irishness. Retweeted and remixed by Blindboy, Instagram artists and the Fontaines D.C. If Ireland was lost, was it Google that would find it?

This reflection aims to present the necessity of important questions; how do we reinvent the future? How do we define our land? As always, maybe history can guide us to revelation. After all, as the late Mark Fisher once put it; “Those who can't remember the past are condemned to have it resold to them forever”.

Some poems

Cleavaun in the snow

Pat

Was it him again?

As I pull over Cleavaun

Or at Paulines,

When Veronica smiles

Or in my chest, on a run.

That’s his ache, I’ve thought

and that breath I push out

Seems like his, when it pulls back in

And that’s where I find him

All these years later

The man I never knew

Not in the stories really

But in the bits,

In the line of mam’s tear

And the shiver when John laughs

In the journey of my thumb

over the threads of his jumper

What a bumpy ride that is,

Thats his thumb, I’ve thought

That’s his journey, is it?

Mont Blanc

Trekking

Up with the sky

Leaning on me

My bag was a bit damp

I packed and left

The rhythm of dawn

Pronounced by gravel

Heavy steps

heavy in the wind

The bells of cattle

Clatter the arrival of noon

Up there

I’d stop, and eat lunch

In the dim of the evening

I’d spot a crook

And sink into the hill

And let the moon

Sink into me

Making dinner - 19:32

She roars the steam

into the extractor

Fusilli bubbles to a supple bend

She’s there with two pots

Rushing the air around her

As they froth and turn

To the stirred intonations

Of her wooden spoon

House as city

Thoughts on Nine Elms, urbanism and how we see the city

This essay intends to add to the debate around Nine Elms. The scheme has been heavily criticised since 2012 when Ballymore Group announced their plans for redevelopment. Much of the criticism has already delved into the technical, political and social shortcomings of the project and for this reason, I won’t be touching on any of these topics.

Instead, what I argue below is a straightforward point; how we see the city impacts the way we engage with it. I start by summarising the basis of this argument, which I see as ontological and then I show how this basis relates to the failures of modern urban theory; the legacy of which pervades schemes like Nine Elms today.

Ontology is flat

Ontology, for those who might not be aware, is a branch of philosophy that is concerned with being. When we talk about ontology we are talking about how things exist, not why they exist, or what they are made of - those questions belong largely to science. I think there is an ontological fallacy that pervades modern urban theory and it affects Nine Elms; but we’ll get to this shortly.

Throughout the history of philosophy, many thinkers have grappled with questions about how things are in the world. Fundamental to this argument are disputes to do with appearances and reality. Take for example an apple. Intrinsic to ‘apple-ness’ are certain appearances like; red, round and crunchy.

Some philosophers have argued that these appearances are all we can know about things and therefore an apple is simply an object that correlates with redness, roundness and crunchiness. These philosophers are broadly referred to as correlationists. On the other hand, realists would say that apples are things that exist independently of what we might know about them. This idea is based on the fact that what we know is limited to what we can observe and therefore; objects must be more than our finite capacity to see things.

Others still, like Graham Harman - a philosopher known for his work in the relatively new field of Object Oriented Ontology (OOO) - believe that objects are not just one or the other - that is; correlated appearances or things in themselves - they’re both.

Harman’s thesis aims to bridge the correlationist/realist divide by introducing the idea of a ‘flat ontology’. This idea states that all things exist in the same way - in that; what they are and how they appear are simultaneously separate and yet interconnected. Thinking in this way is very unintuitive and seems like total gibberish at first. How can something be two things at once? The answer, argues Harman, is found in the physics of spacetime. If time is a linear continuum, then to exist is to be in a constant process of becoming. It follows, then, that for an object to be in this world means that it is simultaneously itself while becoming something different.

The idea of a flat ontology reconfigures the way we think about objects. In particular, it radically challenges the ways we conceive of parts and wholes. The notion that a city like London is ontologically greater than the sum of the parts that make it, for example, is commonplace across the western world. But when viewed through the lens of a flat ontology, this perception breaks down and no longer makes much sense; for instance, to think about parts and wholes as being greater or less than one another implies that certain objects are of intrinsically lesser-importance than others.

Reality, according to Harman, appears to defy this way of thinking. How can a house be intrinsically less than a city? The answer is that; unless we’re talking about ideals, it can’t be. If we place ‘the city’ on a pedestal of transcendent importance, then we must accept that we are doing so within the realms of idealism, not reality. This is what I see as the ontological fallacy, mentioned at the beginning of this piece. It is to conflate the appearances of the world with the reality of the world.

But how does this fallacy affect urban planning? The answer lies in the context from which modern planning arose and a detour is required to fill us in.

Seeing like a state

Scientific and technological progress during The Enlightenment gave rise to, among other things, a new capacity for state control. High Modernism - described by some scholars as an ideology characterised by its confidence in technology, bureaucracy and specialist-led governance - gained traction during this period among the upper echelons of society. As James Scott describes in ‘Seeing like a State’, this ideology became the foundation on which modern statecraft in Europe was built.

The reason for this, argues Scott, was that prior to the enlightenment, society was immensely difficult to understand in clear, quantifiable terms. Technological and scientific advancements changed this, making legible to those in power the landscape, demographics and finances of the state they governed. This process of ‘making legible’ that which was previously opaque involved the application of various techniques that simplified reality into abstracted vignettes such as maps, standardised metrics and indices. The High Modernists were convinced that this newfound legibility was society’s ticket to a utopian future - one which was, above all else, comprehensible and malleable.

The process of mapping and standardising transformed the way local authorities saw their cities. Many European urban centres were renovated in order to rid themselves of their organic, seemingly chaotic and disorganised order - Paris being possibly the most famous example of this. Making cities legible in abstracted terms meant that they were easier to govern. Authorities understood the lay of the land with a degree of precision suitable to bureaucratic management and this helped leaders make better informed economic, social and political decisions. New cities, such as those in the colonies of European nations were designed as gridded blocks, simplified and logical in form.

This new urban design profession championed standardisation, clarity and efficiency and this inevitably gave rise to homogenisation. Cities in India, Brazil, Australia and the United States had differing densities and scales but were fundamentally similar. Variability, after all, meant complication and this was the ultimate faux pas of the High Modernist clerics in charge of planning society.

Urban planners viewed ‘the city’ as a singular object of design. It was placed on a pedestal of transcendent importance relative to the individual components that made it and by doing so, these designers had embraced High Modernist idealism and not the more nuanced reality before their eyes. In other words, High Modernism was predicated on an ontological fallacy and conflated the appearances of the world with the reality of the world.

House as City

Though viewing a city as a singular object of design might be idealistic and flawed, perhaps large scale urban planning is impossible without an overarching narrative to guide it? High Modernist idealism certainly structured modern planning, for instance, bringing with it enhanced organisation, clarity and efficiency - all no doubt necessities when building at the scale and speed required by contemporary societal conditions. However, it also reduced the complexity of cities; making them diagrammatic and two dimensional and it was on this basis that modern urbanism was criticised most by people like Jane Jacobs, Colin Rowe, Robert Venturi and Aldo Rossi. Despite all of this pushback, I believe the legacy of High Modern urban planning still pervades many developments across the globe today.

I think the underlying reason for this is quite simple; investor risk. On the face of it, nobody is willing to invest their capital in an inefficient plan or something that lacks a grand narrative to structure it. The straight-lined, right-angled and mono-variate nature of modern urbanism may have initially appealed to the Enlightenment-era local authorities, eager to increase their control over society. But over the years, and with the steady development of capitalism, it appears the benefits of simplifying urban design have also manifested in the returns on investment of private developers.

On the face of it, Nine Elms doesn’t appear as simplified as the gridiron urban plans of the past. The crooked and curved facades that surround the old Power Station do not scream ‘efficiency’. But these Starchitect designed apartment buildings have been carefully factored into the overall feasibility plan that has allowed for such pricey buildings on the basis that their ‘High Culture’ significance will raise the overall land value of the site. This thereby justifies extortionately high retail prices which then offset the losses made throughout the rest of the development, where some social and affordable housing has been allocated to meet local authority requirements.

It is only when you scratch the surface of Nine Elms that the High Modern spectre raises its head. The financial balancing act described above reveals something telling with regards to how the scheme has been conceived. Like the High Modernist planners, it appears that the developers of Nine Elms see this project as a singular object of urban design and as I started this piece, the way we see impacts how we engage. The success and viability of the project as a caricatured whole seems to have mattered most to the makers of Nine Elms and the result is a scheme that appears out of step with everything around it, detached from the character of the area. Perhaps Harman’s flat ontology is a clue to why this is? If reality requires nuance in order to grasp it, then maybe we need to stop viewing our cities as caricatured objects and embrace the complexity and contradiction that the great critics of High Modernism espoused. Bottom-up and self-determining; house as city.